When I was a kid, my parents bought me a Euro-themed Monopoly version to play with my sister. It was the time countries in the European Union were about to change currency, and I remember it as a huge thing. Plus, we finally owned our own version of Monopoly, one whose cards and board didn’t need to be held together with scotch tape.

A few games of it, though, were enough for me to despise it for life. I’ve never been lucky with dice rolls, while my sister was in very good terms with the goddess of fortune. And Monopoly is not the kind of game where you can make up for bad luck with good choices: the strategy is one and one only.

You must buy as much as you can, hoping to end up on the best spots in the board before your opponents do. The game is very skewed to quickly produce a rich gets richer dynamic, no matter how many rules you can add to try and make it fairer. My sister, for example, liked to extend my virtual financial struggling by lending me money from time to time: she knew she would get them back very quickly.

I’ve always thought it was a side effect of Monopoly not being a thoroughly designed game: the studies about balance and game design weren’t a thing back in the early Twentieth Century, after all. You can imagine my surprise in finding out that the sense of frustration players get from Monopoly is actually by design. A feature, rather than a bug.

The history of the game

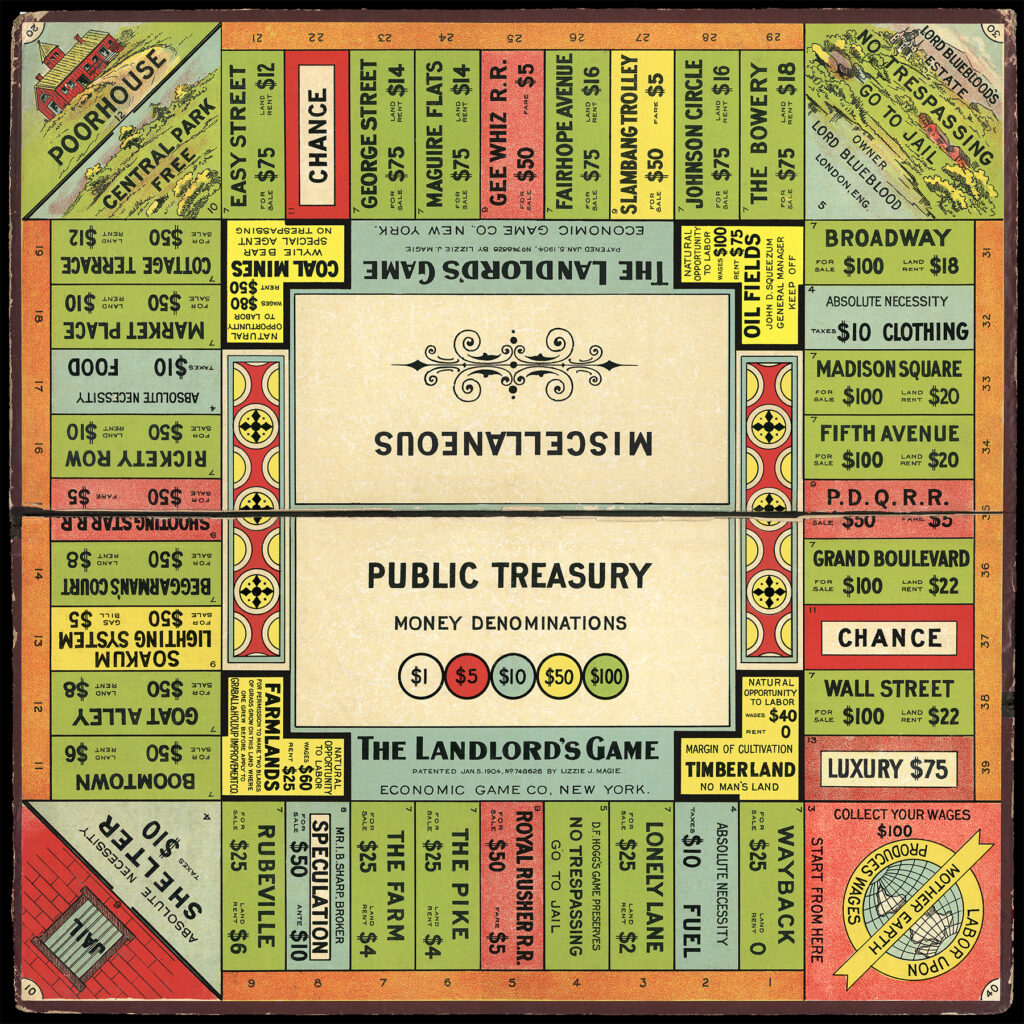

In its original formulation named The Landlord’s Game, Monopoly was meant to induce frustration, boredom and hopelessness in the players. The aim was to show how bad it is a situation in which someone can profit by owning something that should be owned collectively: the land. Elizabeth Magie, the woman who invented it, was a fervent supporter of Henry George, who was convinced that landlords were a class of parasites who profited on people’s basic needs without contributing to society in a meaningful way.

The Landlord’s Game was a piece of propaganda that was originally distributed among students of Economics in the East Coast. Its rule were tweaked from time to time to simulate scenarios and a few ways in which it could be made “fairer”, until it came into the hand of someone who saw the opportunity to profit from what originally was an educational game: mr. Charles Darrow.

He completely twisted the premise of the game, presenting the idea of bankrupting your friends and profiting on their misfortunes s an inherently good winning strategy. He also changed a few of the game graphics (the man with the stache and the top hat, the “Go” square, etc.), even though he never compensated the person who helped him fairly. Darrow published the game with Parker Brothers, which was already big and powerful enough to completely erase Lizzie Magie and her contribution to the genesis of the game.

In a certain sense, we can see how The Landlord’s Game was a successful metaphor for a greedy society, and how that same greed stole the credit from the person it was due to. A metaphor working on two levels. Theory and practice.

The story of the game origins would be much more frustrating than the game itself if it wasn’t for another twist induced by the same greed. In 1973 Ralph Anspach, a professor of Economics, invented a game (Anti-monopoly) with a formulation more similar to the original The Landlord’s Game, and was handed a cease and desist action by Parker Brothers.

Anspach had no intention to comply, and decided instead to research the origins of the game to see if he could catch Parker Brothers red-handed. This allowed him to re-discover the history of Lizzie Magie and her game, and how she was done wrong by Charles Darrow and Parker Brothers.

Is all the story I’ve just told enough to re-evaluate Monopoly as a game? Definitely not: knowing that it was designed to be frustrating in some way allows me to feel that way the (very few) times I get to play it. This was Lizzie Magie’s motivation to invent the game, after all, an who am I to disagree?

Still, it was good to have a motivation and a justification for the bad relationship I have with the game (it’s the one I bring up when I want to highlight anything that’s wrong in game design).

Be First to Comment