I had great expectations about Stuart Turton’s second novel. And it delivered.

I’ve expressed my love for murder mysteries quite a lot across a few posts on this blog, but despite not being able to resist, I always feel like something’s missing in them. They tend to live “in the void”, usually don’t depend too much on the context around them. They’re a bit formulaic: the murder usually stems from greed, hatred, love, or a quest for revenge, and the murderers usually take advantage of their wits, stealth and deception to try and get away with it. It’s not a coincidence that many of them, often the best ones, tend to be set in isolated places to restrict the cast of possible suspects.

Still, the battle of wits between the detective and the murderer is often enough to silence the inner voice that wants a more complex theme to the story. I find myself turning page after page as I try to inspect every little detail that can lead me to figure it out before the reveal, which usually comes in the form of a lengthy exposition by the detective.

This is part of the reason why I was blown away as I read “The 7 1/2 Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle“: not only the events leading to the solution are crafted in a quite original way, but it also ties the story with the concept of revenge and obsession as opposed to forgiveness. I still think that the way it was laid out (as a long explanation after the murder has been solved, the tension released) made it a bit confusing and in a way affected both the exploration of the theme and the mystery itself, and this is why I’ve been wanting to read “The Devil and the Dark Water” for a while. Will it deliver, I asked myself, while tying a compelling and original theme to the mystery?

Long story short and spoiler free: it did, but with a few caveats.

The Book

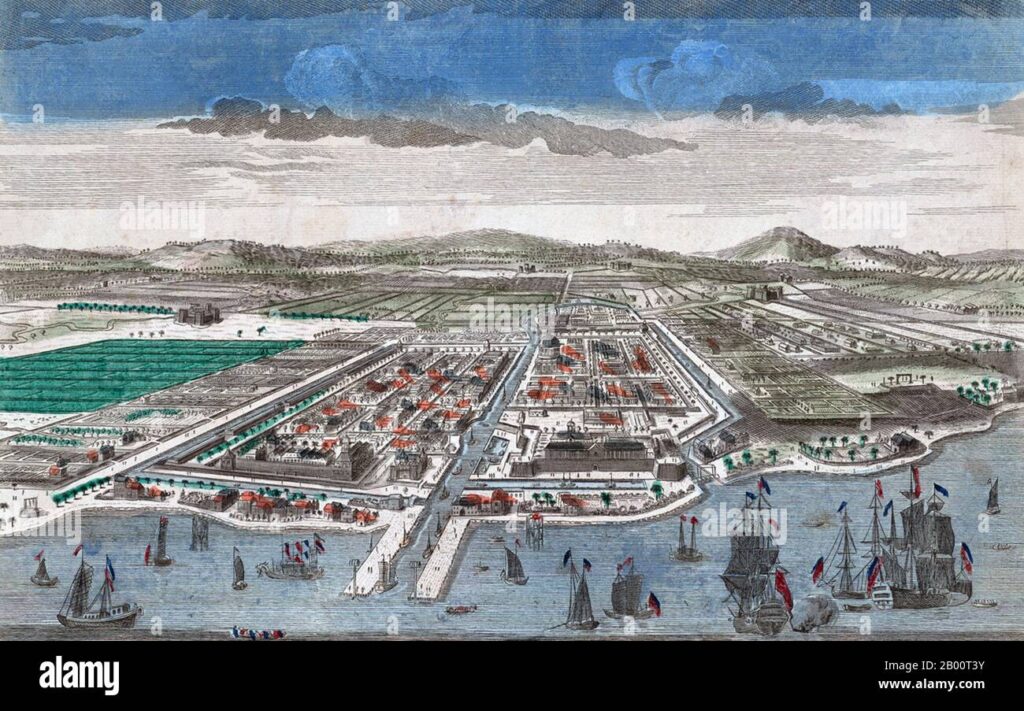

From now on, I’m not sure I can keep it spoiler free, so read at your own discretion. While “7 1/2 Deaths” was not too precise about its setting in time, as it pretty much took place in an imaginary huge mansion (see?), “The Devil and the Dark Water” starts off in the year 1634 in Batavia, a Dutch colony in the Indian Ocean which correspond to Jakarta. Governor General Jan Haan is about to board on the Sardaam to get back to Amsterdam with his wife Sara and daughter Lia after 15 years in Batavia.

He’s supposed to be admitted to the Gentlemen 17 , a sort of council of the most important men in the Dutch Provinces, as long as he delivers a special prisoner: it’s Samuel Pipps, a renowned investigator which is detained for an unknown crime, possibly treason.

The Sardaam appears to be doomed since the very beginning, when the devil itself seems to be speaking through a carpenter with leprosy, which auto-combusts right after the speech. Then a symbol associated with Old Tom, a devil that had been haunting the provinces in the Netherlands, appears on the ship’s sails as soon as they’re unfurled. So many people ask governor general to not depart on that day on that ship, but to no avail. Jan Haan is a man full of determination, and can’t wait to get to Amsterdam.

As you might expect, many inexplicable things will happen on board as soon as the ship leaves the port. The leper reappears at the cabin windows, livestock is slaughtered while in their enclosing, a ghost ship chases the Sardaam.

Meshing a Theme in

Stuart Turton once again asked me to trust him with a few leaps of faith, but the story he went for made it worth it because of how well the mystery was tied to my understanding of the mindset of the late Renaissance. The central part of the book sees the popular superstition of Seventeenth Century protestants and religion in general opposed to the search for a rationale explanation about the events occurring on board. It’s kind of an anticipation of the Enlightenment and how it’s steadily going to change the mindset of Europeans after centuries of appeals to faith and superstition rather than reason.

The final solution of the mystery, of course, involves no demon, not the ones religion warns us about at least. It’s all a product of one of the finest human minds with a thirst for revenge after their family was destroyed. To close the loop, this family was destroyed by another scheming of the powerful Jan Haan to exploit popular superstition to get richer and crush their rival families. It was a plot with the right touch of irony, and it worked for me. It made me completely forget about a few improbable logistics happening inside and around the ship, which in my opinion is just the proof of the suspension of disbelief in action.

Last but not least: controversies

Many people weren’t satisfied by the ending, by how Sara, Lia and Arent accepted to team up with Sammy/Hugo and Cressjie/Emily to get revenge over corrupted noblemen exploiting their power over people and popular superstition. I get where it comes from, because it’s a sort of resorting to “private justice”, which is something I’m firmly against. But for me, it was fine as an ending for “The Devil and the Dark Water“.

For starters, the book hints at many cases Pipps and Arent solved together, and this kind of ending keeps the door open for more to come. And if more cases come, a good theme to explore could very well be private justice and how they self-proclaimed themselves judges and executors. But I realize how this hypothesis is quite far fetches, almost as playing the devil’s advocate.

Sticking to this book, I wasn’t disturbed by their final decision because I’m into people with grey morals. And I see why Sara and Lia would give up a bit of their morality for a life of adventures and, especially, not being considered inferior to men.

Sara was already considering leaving Jan once they got in Amsterdam, and as much as a woman leaving her husband is (fortunately) nothing to be frowned upon anymore in the XXI Century, I don’t think the same could be said for society in 1634. Yes, protestants were the one more “liberal” about divorce, but I don’t think they saw a woman divorcing a man as acceptable as a man divorcing a woman.

But the main reason why I wasn’t upset by “The Devil and the Dark Water” because I just took it for what it was: an interesting story, in which the protagonists aren’t necessarily supposed to be taken as role models. Especially because there’s no such thing as people completely good or completely evil.

Be First to Comment